Sunday, February 21, 2010

Saturday, February 20, 2010

8 of 8 - What's in a Word? Dissidence, 'Denial,' and Health on a Poly Planet - From The G Tales

You call me ‘promiscuous,’ I call you ‘dishonest,’ a poly person tells the average person who believes that monogamy is the only natural way to love.

You call me ‘denialist,’ I call you ‘believer,’ a dissident person tells the average person who believes that HIV is the only cause of AIDS.

When you call AIDS Dissidents by their own name you exercise leadership in the sexual freedom movement.

Alternative lovestyle communities ignore AIDS Dissidence at their own peril.

From private conversations

Part Eight

“You believe you are a leader in the Polyamory Movement, correct?” asked G as we resumed the conversation.

“Yes,” I replied.

“Yet when you are calling dissidents denialists you are not exercising leadership in the sexual freedom realm.”

“Why not?”

“How would you feel if all of a sudden by some specious misnomer you found you were a leader in the Promiscuity Movement instead?”

“I wouldn’t want to be a leader in that movement, of course.”

“Right. You got it. Wouldn't that misrepresentation of who you are to the world produce a barrier in communication?”

“Yes, it would put me in a place where even affirming my right to exist is a problem, let alone delivering my possibly important message.”

“Yes, it would put me in a place where even affirming my right to exist is a problem, let alone delivering my possibly important message.”

“Now you’re getting it,” G replied, “but there is more to that,” she continued.

“I’m listening,” I said.

“Health and love are related. How we practice love has an effect on our health, and how we keep our health has an effect on how we love. This applies at the individual, the community, and the planetary level, would you agree?”

“Yeah?” I hesitated, not sure what G was getting at.

“Well, the current interpretation of AIDS has kept the world locked in fear for decades. Think of those sex players in the younger generation who’ve never experienced fluid-bonded sex.”

“Ouch!” I said.

“Ouch!” G repeated. “You know how rarely I fluid-bond. And yet, the most remote ever memory of what it feels like, of the complete communion and interpenetration that happens when one makes love freely and all the fluids are exchanged, is what keeps me wanting to stay alive and healthy--so that, if the type of relatedness that warrants fluid-bonding ever arises again, I can do it at no risk for others or myself.”

“I can’t disagree with you on this one G,” I said, “and I don’t know that anyone who has experienced fluid-bonding in a positive way honestly can.”

“So if we can construct, in rigorous scientific terms, another theory of AIDS that interprets fluid-bonding as a message of love--a message of health, then we can use this scientific interpretation as another way to demonstrate how significant Gaia theory is in relation to the diseases that affect us all.”

“Gaia is quite tired of us especially when we don’t seem to listen to the message of her illness and discomfort as manifest in climate change and global warming,” I commented.

“Precisely,” G said, “if we can better learn the arts of loving that allow us to practice fluid-bonding as a form of holistic health for ourselves and our erotic communities, then we can make Gaia more comfortable with our presence, because we will be busy practicing these arts in their various forms rather than frantically consuming products that do not make us happy and contribute to the excessive production that causes climate instability to begin with.”

“What I hear you saying is another version of your sound-bite, ‘a world where it is safe to love is a world where it is safe to live.’ In other words, if we can enlist science to make the world safer for the arts of loving then it will become a world safer to live in as well.”

“Yeah! You got it!” giggles G.

G and I finally giggle together. This has been a heck of a conversation. I feel exhausted. But then, isn’t that the essence of being poly? Endless conversations, debates, open heart disagreements, and that’s how we become cohesive as a movement and we grow.

“What's in a name? You said.”

“Right. What’s in a name?

“The AIDS Dissidence Movement has a name.”

“G, do you mean that calling movements, entities, people by their name is science, it is a form of knowledge we owe others different from ourselves?”

“Yes.”

“Let’s get back to square one then, and begin to see what the argument of your book looks like if the AIDS Dissidence Movement gets to be called by its own name.”

“Let’s.”

“Thank you, G, it’s always good to talk to you. You never seem to give up on thinking with your own head.”

“Sometimes I get headaches,” she giggles.

“I’m sure you do,” we giggle together. “What do you do about it?”

“I use what my friend Alan calls ‘woo woo’ remedies. I get a massage, some craniosacral therapy. I meditate, swim, walk. What about you, my dear, my patient friend, are you ready for the holidays?”

“Yes, G, now I am.”

“I looked at Gaia’s waters today, she’s still patient, and she sends her blessings.”

End of Part Eight, G Tale # 5

End of Tale

A former AIDS patient speaks out on TV, Atheatos Kosmos

Maria Papagiannidou, author of Goodbye AIDS

Disclaimer: This Tale does not constitute medical advice in any way. Readers are invited to consult their own healers and health care providers.

References: For scholarly and scientific references to contents and theories referred to in this dialog, refer to Gaia & the New Politics of Love, whose bibliography lists all sources involved.

Thursday, February 18, 2010

5 of 5: We Are Everywhere: A Fiveway Review of A History of Bisexuality, Bisexual Spaces, Look Both Ways, Open, and Becoming Visible

Cont’d, Book Five: Beth Firestein’s Becoming Visible (Columbia University Press, 2007.)

By Jonathan Alexander and Serena Anderlini-D’Onofrio

Has appeared in Bisexuality and Queer Theory, a special-topics issue of The Journal of Bisexuality. Re-published with permission of Routledge, New York.

Last but not least, this review will consider the collection Becoming Visible (2007), which was put together for the purpose of empowering the counseling profession to provide health services to people like Jenny, Christopher, Jemma, and others, such that would help them actualize their ideal amorous configurations rather than make them feel guilty for desiring them. The collection takes the lead from what manifests as the urge that most clients bring to a counselor’s table, rather than what the counseling profession at large might consider appropriate. As editor Beth Firestein announces at the onset of her introduction, “our clients are no longer coming to us because they want to be ‘normal.’ They are coming to us because they want to be whole” (xiii, original emphasis).

As a person who, in principle, does believe in psychotherapy, and who, out of a desire for integrity with her own chosen communities and identities, has practiced individual forms of individual therapy only in the context of co-counseling with members of queer, bi, and poly communities, co-editor Serena Anderlini-D’Onofrio could not be more supportive of this kind of endeavor, and hopeful that the very serious studies and research contained in this volume make a significant impact in the profession of psychotherapy, so that more counselors are available to help people like her. “Whole” stands of course for fulfilled in one’s aspirations in creative, imaginative, unique ways, regardless of any normativity, and, in particular, heteronormativity. It is a tall call for any therapist, since one’s personal experiences have an effect on the span of one’s imagination, and that tends to trace the contours of one’s belief systems as well. So, while one cannot imagine how counselors who believe in “converting” gays to heteronormativity (like those the film Bruno makes fun of in a crucial scene) could be impacted by this book, one can certainly see how many liberal therapists open to the idea of wholeness as the goal of a counselor’s work, can find in the book’s pages the data, information, tools, and evidence to become more effective in their job. Besides this, the book also of course empowers those accustomed to coaching, co-counseling, self-counseling, sharing with confidantes and in support and social groups, pillow talk, and other informal ways of accessing emotional resources, to find pot what it is that they need to get over a stumbling block in their psychological progress and development.

The book’s sections include an overview of critical issues in counseling bisexuals; a central section, “Counseling Bisexuals Across the Lifespan,” that establishes bisexuality as a viable sexual identity acceptable to clients and therapists no matter for how long and at what age it is adopted to describe oneself; a section on the psychological situations faced by bisexuals who are part of cultural, racial, or ethnic minorities; and a section on diversity of lovestyles among groups of bisexuals.

For the sake of this review, we will focus on three chapters in the volume. Chapter 11, “Addressing Social Invalidation to Promote Well-Being for Multiracial Bisexuals of African Descent” (207-228), by Raymond Scott, emphasizes the challenges people of African descent face in the United States when they identify as bisexuals. In the context of critical race theory, the author emphasizes how, when in the culture at large one is exclusively or at least primarily defined by color, any other non-normative self-definitions become fraught with the risk of being considered too deviant to be taken on, with the ensuing consequences of forced duplicity and closetedness, as in what is known as the “down low” lifestyle. This situation in turn tends to produce self-destructiveness, loss of voice, invalidation, and all the severe emotional and psychological challenges these entail. It is very important, the article claims, to begin with a self-defined notion of race. The author models this by describing all people of African descent in the Americas as multiracial, including African-Americans who live in the United States. Historically, by definition, this is the country where “whites” and only whites have been defined by “purity.” Once this multiracial, self-defined multiple notion of race is recognized, affirmed, and embraced, the coming-out process of a multiracial bisexual client can begin to take place.

Chapter 17, “Counseling Bisexuals in Polyamorous Relationships” (312-335), by Geri Weitzman, focuses on the segment of the bisexual population that defines itself as polyamorous and whose members practice some form of responsible non-monogamy or multipartnering. The chapter makes good use of a wide spectrum of data collected in well described informal online surveys. It offers an articulate typology of the polyamorous population and the kinds of discrimination it faces. Further, the chapter explains why poly people believe that practicing polyamory contributes to their stability and mental health; it describes their main concerns in a world unfamiliar with their orientation; and reports the incidence among polaymorists of individuals who identify as bisexuals: 51 percent of the total sample according to the survey (317). Weitzman’s research also contributes to dispelling the myth that polyamorous bisexuals behave like what Fritz Klein calls concurrent bisexuals, namely that they need to be involved with a male and a female at the same time to be whole. Another dispelled myth is that polyamorous bisexuals are more at risk for sexually transmitted diseases than others. The report is that 71 percent of respondents affirm that their lovers’ gender does not matter. It was also found that enhanced awareness of safer-sex practices have successfully protected polyamorous bisexuals from being more affected by STDs than the general population.

Chapter 18, “Playing with Sacred Fire: Building Erotic Communities” (336-357), by Loraine Hutchins, focuses on counseling participants in “social or friendship networks that include sharing of sexual experiences between network members in various combinations” (336). The author adeptly introduces the concept of erotic communities. This trope shifts the focus not only from the sexual to the erotic, but also from the private (from what is supposed to happen behind closed doors, the famous ‘primal scene’ that would be cause for childhood trauma according for Freud) to the public, or at least to an open space where erotic energies can be shared by multiple participants in an amorous game. With her subtle awareness of and respect for erotic communities based on notions of tantra and sacred eroticism, Hutchins engages a queer terrain indeed, as she proposes that counselors revise the prevalent notion of the orgiastic as the ultimate primitivism and negative loss of self, for a positive notion that revises this experience as one deeply connected with the divine and the sacred. What happens to the cultural construct of sexuality, with its embedded paradigms of monosexuality and monogamy, when multipartnering in an eroticized space is revised as a religious experience? Hutchins examines three sacred-sex communities, Carol Queen’s San Francisco based “Queer of Heaven,” the Pennsylvania based “Body Sacred,” and “The Body Electric School,” also based in the San Francisco Bay Area. She points out that leadership in the creation and development of these intentional communities has consistently been bisexual, and that the effect of the work of these communities in the culture at large has been that of teaching anew forms and styles of the arts of loving, some of which were quite well known in cultures ancient or other than the West. In other words, when all life is recognized as a form of the sacred, as it was in classical antiquity and still is in Tantric Hinduism, then bisexuality, like other plural forms of erotic expression, are every bit according to nature, or, in secondo natura, as Cantarella’s original title explains. This erotic knowledge, we would like to add, is indeed part of the sacred, as it helps to assuage pernicious fears that stand in the way of practicing love sustainably. This knowledge helps to control risks involved in producing love in an age of uncertainty like our own, when production of this essential element that all life shares is especially necessary.

The width of topics and disciplines, the range of interests and perspectives deployed in the reviewed books suggests that the intersection of bisexuality and queer theory is a space populated with multiple minds that vibrate together as their intellectual visions examine and gradually transform our cultural notions of the sexual, the amorous, and the erotic.

Works Cited

Angelides, Steven. A History of Bisexuality. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Baumgardner, Jennifer. Look Both Ways: Bisexual Politics. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007.

Block, Jenny. Open: Love, Sex and Life in an Open Marriage. Seattle: Seal Press, 2009

Cantarella, Eva. Bisexuality in the Ancient World. Yale University Press, 1992. (Originally published in Italian as Secondo natura, 1988.)

Firestein, Beth, ed. Becoming Visible: Counseling Bisexuals Across the Lifespan. Columbia University Press, 2007.

Garber, Marjorie. Vice Versa: Bisexuality and the Eroticism of Everyday Life. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

Hemmings, Clare. Bisexual Spaces: A Geography of Sexuality and Gender. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Klein, Fritz; The Bisexual Option. New York: The Harrington Park Press, 1993.

Also appeared in SexGenderBody.

Republished here with thanks to Arvan Reese.

Also appeared in SexGenderBody.

Republished here with thanks to Arvan Reese.

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

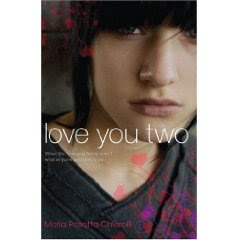

Love You Two, by Maria Pallotta-Chiarolli - Book Announcement

Set in today’s multi-cultural, multi-sexual Australia

When Pina was a little girl, her mum used to sign cards and notes to her and her younger brother Leo with the crazy line, 'Love you t(w)oo.' It was supposed to make them feel like their mum had heaps of love for both of them, that she loved them equally. Well, that's okay when you love all your kids. Actually, that's the way it should be. Then a chance glimpse at an email unravels what Pina thought she knew about life and love. What happens when your Mum loves your dad as much as ever, but is also in love with someone else! And what do you do when you run away to stay with your uncle only to be thrown into another, unexpected, world where there’s a lot more to sexuality than gay or straight!

Pina’s friends think she’s lucky. How many families get along the way hers does – how many parents are as free-spirited and happy as hers? Pina's always loved her mum for fighting the 'old wog ways' of her grandparents, and making sure Pina has an easier time growing up. But can her family and her friendships survive what she has discovered? And what does it all mean for Pina’s own life?

Two siblings, two boys, two cities, three generations, four friends:

how many versions of love?

Love You Two was inspired by Maria Pallotta-Chiarolli’s fifteen years of community work and academic research and publishing in sexual, family and cultural diversity in

Price: $18.95 ISBN: 9781741660715

Publisher: Random House Australia

Available from Australian bookshops and their online bookbuying services.

Please support

http://www.hares-hyenas.com.au/book.asp?RecID=16230

or Amazon.com

http://www.amazon.com/Love-You-Two-Maria-Pallotta-Chiarolli/dp/1741660718/ref=sr_11_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1231456944&sr=11-1

or Independent Publisher’s Group for US distribution:

http://www.ipgbook.com/showbook.cfm?bookid=1741660718&userid=F31388E8-3048-6445-434BBD3D8F2F897B

Echinacea & the Swine Flu - From The G Tales

“when we see things in [a Gaian] perspective, it becomes very easy to understand the basic principle of holistic health. If an individual is a cell in a superorganism, his or her disease cannot be a foreign agent, for all agents are part of the larger entity of which that individual is an element”

from Gaia and the New Politics of Love

The periodo lectivo is approaching and G tells me her classes are starting again. She was at the school office and found it plastered with notices discouraging people from kissing on the cheek and shaking hands.

“It’s the swine flu” she told me on the phone, “nobody wants to be held responsible for someone getting it, and so they post those disclaimers so that if you do get it, you can’t blame them.”

“But people are getting the swine flu, G,” I replied, “they’re even dying from it, haven’t you heard?”

“Of course I have” she said, “but do you think that those disclaimers really help?”

“Well, what’s wrong with reminding people to wash their hands, keep from getting too close to someone who could be contagious? I got friends who almost got it, it was scary, loads of tests, anxiety, we all got a bit nervous and wary. It was hard to keep one’s cool. But nothing really bad, it turned out everyone was ok. How about you? Anybody you know?”

“Oh yeah, my massage therapist got it, she had to quit her job. She was abject. She got depressed. She called me and I spent hours with her, then I went out and got a bottle of Echinacea for her.”

“Your massage therapist? The one who calls you mi abuela postiza, my pretend grandma?”

“Yeah, and imagine, a week earlier I had a two hour massage with her. As soon as I get into the parlor, we hug and she tells in how much pain she is. I sit her on the table and ask her to show me where it hurts. Then I work and work and work on her, the neck, the chest, the shoulders, the back.”

“You mean you start massaging her?”

“Yeah, what else? She was sick, she needed the help.”

“But this was your massage time, no?”

“It was, and there I am, giving a massage to my massage therapist. Getting her well enough that she can do me, eventually. And telling her not to worry, that it’s just fine--I had offered to exchange with her many times because I knew she was overworking.”

“OMG! What a situation. And then she gets the swine flu?”

“Well, I found that out later. Meanwhile, I didn’t get anything--so no harm done. And when I hear she has it, I go out and get Echinacea for her. A little bottle.”

“Oh, yeah, I got that too. A special dosage, even though this time, with the swine flu being so potent, I didn’t really have a lot of trust in these flimsy remedies.”

“Flimsy? You know we’ve been taking it for years now. Once in a while--just so enough of it is in circulation that the immune system can respond before anything happens, before any microbe has its way.”

“Don’t tell me that you have such faith in it. I take it too, but it’s more as a way to touch wood for good luck--a superstition if you want.”

“Really? But don’t you know that it’s indigenous knowledge. Echinacea comes from the center of a daisy, it’s the powder found in there. It has been used for immune system strength by generation after generation. This has been known for centuries. It’s time-tested knowledge. Better than laboratory, because there’s so much history of it having been effective.”

“Nobody knows why though.”

“If you consider that a problem.”

“Could be a problem. Perhaps one could run some experiment as to why.”

“Or, those ultra-scientific all-knowing health authorities could simply collect data from people who regularly take Echinacea, and find out how rare the flu is among them compared to those who don’t.”

“Are you sure that’s so?”

“It is well known in the holistic health community. Everybody knows and takes it. And take a look at them—I mean people who do holistic health--they don’t call the doctor every day, they’re not afraid to get sick, they often radiate health and resist pathogens much better.”

“Yeah, I must admit their lives are not as medicalized as those of some other people I know. In any event, it sure would be worth trying to get some data. I know I don’t get the flu often. How about you, G?”

“I used to get it. Before Echinacea. When I used antibiotics. Now I don’t. And I use all kinds of remedies--there’s one for every situation, once you get the knack of it. And my daughter. A flu after a flu after a flu. Lots of antibiotics. Until she was ready to go to college. And then I said, ‘what’s the point of sending her to college if she’s always in bed?’ So we stopped antibiotics, and did Propolis topically to quench throat infections, and Echinacea when she was well, as a preventative. It was quite effective. She graduated on time and with good grades!”

“But then, why do you think people still do antibiotics so often?”

“They’re afraid, they’ve been taught not to trust their immune system. They’re used to depend on meds. Sometimes it’s as banal as the taste of these remedies. People are used to pills. A potion--with its own taste and flavor--scares them, it appears medieval to them, a witch’s brew.”

Giggling over the phone . . . “A witch’s brew” we giggle together.

“And witch’s brew it is,” I continue, “when you think about it, the only evidence being experience, tradition, indigenous knowledge, historical evidence--opposite of what modern science understands.”

“And who’s short of understanding? Indigenous knowledge works. Just because something’s modern doesn’t mean it’s good.”

“Take it easy, G. You tend to get carried away. Allopathic medicine is not worth bumping heads against. You never know.”

“Of course my dear. You know my weakness. An accident, a trauma, a birth defect, a sudden outbreak: allopathic medicine is much faster, has an immediate effect. Take my cousin’s club foot that she was born with,” G said. “They open up, they switch the tendon to the right position, and the baby’s gonna grow with a regular foot, like everybody else. Can you imagine not having access to that? Having to watch your baby grow up with a twisted, upside-down foot just because you cannot get surgery?”

“Oh my gosh, that would be horrible, G. Good to hear that surgery went well. Doesn’t matter how many massages, manipulations . . . ”

“Yeah, and doesn’t mean that applies to all situations. Sometimes the effects of that kind of aggressive interventions are more than secondary. Sometimes they override the benefit. Remedies are much more gradual and benign, with more positive and durable effects.”

“And how about those images in the office. Were you telling me how you they made you feel?”

“They made me feel terrible. Here in the Caribbean people touch when they shake hands and kiss each other on the cheek, once. It’s a bonding ritual that is good for one’s sense of connectedness, immunity and health. Now, with the excuse of the swine flu, public health officers are trying to take that away. Those posters made me feel depressed. And that’s bad for one’s immune system. I’m sure I’m not alone. Others probably feel their social manners are being criminalized in some ways.”

“Oh, one kiss you said? It’s three in France and two in Italy, correct?”

“Yes,” said G.

“I wonder what’s being posted there?” I asked.

“I bet not much” she replied. “I’m just speculating, yet I can’t imagine the French or Italian government criminalizing affectionate behavior--what has been considered good social manners for centuries. But you never know. Have no direct reports at this point.”

“Have you heard any comments? From colleagues at the university, I mean, people you know?”

“Not really, I’ve seen people pull out these little bottles of hand disinfectant and rubbing their hands with it. They pour it on mine as well, and I comply. It feels clean, has a strange smell. I abstain from getting my own. And you know, as I watch all this, as I hear that people are dying from the swine flu, that it is very serious, that it was almost fatal to somebody as close as my pretend granddaughter, I get really upset. First of all, the flu could not be so serious if the world was in better heath, I mean if the biota was stronger and more whole, if the web of life where we are embedded was more wholesome and healthier. And then, for %^&**’s sakes, at this time when the threat is really serious, what would public health authorities lose from making some surprising declarations.”

“Declarations like what?” I ask.

“You know, like, that they really don’t know why, but they hear reports that Echinacea is very effective, that people in the holistic health collective have something to offer, and that they, the authorities--those in charge of public health--are willing to break a lance. That they are willing to make fools of themselves and endorse a witch’s brew, put their weight behind it, so the public at large--I mean those who commonly believe in authority--can finally benefit.”

“Arrgh, what a scene you’re making, G. Now suppose the surgeon general recommended Echinacea on CNN tomorrow, what do you think would happen? Wouldn’t everybody think she’s gone crazy? Would your average Joe who watches TV all day go and get the remedy? Or would this rather end up causing a big ruckus in the high spheres--with her being fired, and some pharmaceutical company declaring her insane and locking her up?”

“Well, I guess you have a point. And yet, they talk about health care reform. What kind of reform? Nothing is going to change if people don’t start to think differently about health. Look at this example. Many people have died of the swine flu. Something as cheap and accessible as Echinacea could have saved some of them. And yet, of those in authority, nobody said a word. I did buy Echinacea for my pretend granddaughter. It’s here on my table. I invited her to come and get it. Hopefully she will, when she’s better and before she gets sick again. But you know, had she heard it in the media, she’d be here already. I mean, isn’t it unconscionable that they haven’t told her?”

“I can see your point. The stakes were high this time. And it’s always on us--we who practice holistic health--to spread the word. And we have no authority. As good old Lillian Hellman would have said, ‘I’d rather make the attempt and fail than fail to make the attempt’.”

“Thank you dear. It’s good to talk to you. Hopefully, it will happen. And meanwhile we have SexGenderBody blog where our voice can be heard.”

Note: This is a fictional dialog and its contents do not constitute any kind of advice. Each person is different and responses to remedies vary accordingly.

End of G Tale # 2

Please note: The time references in some of the G Tales are off because they first appeared in SexGenderBody

Reprinted here with thanks to Arvan Reese

Sunday, February 14, 2010

Why Is Mono Poly Too? - From The G Tales

“one must learn to love one before one can love many,” from Intimate Dialogs

“amor ch’a nullo amato amar perdona,” from La Divina Commedia

“love, that releases no beloved from loving” (Allen Mandelbaum tr)

I have this friend, her name is G. G for gentle. G for giddy. G for “gay.” G . . . for g-spot, or was it g-string? Anyway, she’s like a little girl, I mean, she’s a bit like a thirteen year old, still has the intensity, the trepidation, the relentless, the hubris, the utopianism of that age. Bless her heart.

She tells me everything about herself. And yet I don’t really know her. She’s a mystery to herself. She’s a philosopher, and yet, she’s still a little girl . . .

The latest about G is that she’s alive and well. She’s actually enjoying the dry tropical season, and thinking about numbers.

“Is mono part of poly?” she asks on the phone.

“How can it be,” I say, “if you’re mono you’re not poly. It’s either poly or mono. Don’t you know about those famous mono partners and the havoc they can cause--how they always manage to spoil the game?”

“But listen,” she says, “the number one is just the first in a series from one to infinity. So if you can truly love many you can love one, because one is less than many. No? If you understand infinity, the number one is easy to understand. It’s just a matter of multiplication.”

“Well G,” I say, “this is a bit utopian. The reality is that we often don’t even have the courage to love one, forget many.”

“I know,” she replies, “but love expands to infinity as well, love that is wishing the best even when nothing comes back, love that is empowerment, fulfillment of the other’s potential, love that is free of desire or possession, love that corresponds to the free vital energy of eros. Love that traverses us and weds us together in the communion of life shared on the gay planet earth.”

“Sure,” I say, “that’s how one is part of many, one love that multiplies for everyone that there is to love, like, say, a parent who loves all of his/her children, no matter how many. But when sexuality is involved, things are not so simple.”

“Let me explain it with Dante” she giggles. She’s so literary. She’s read too many books. Her mind’s so convoluted nobody can really follow her. “Three was his favorite number, did you know? Perfectly balanced and open. He’s a bit of a pain in the butt, when you have to study him in school, you know, but he did get something right: numerology.”

“What’s so good about three?” I ask.

“Well, it’s the first of the truly plural numbers, the first that looks upon the infinity of subsequent numbers and is part of them. There is the singular, ‘one,’ the dual, which is, in some cases, still singular in language, as in ‘a couple,’ then there is the plural proper, what cannot be reduced to the singular, except in poly language, where you find words like ‘triad,’ or ‘quad,’ or ‘pod,’ to indicate relationships that include more participants than a dyad, or couple, can.”

“And what does this have to do with Dante?” I probe, “was he poly?”

Giggles. Then silence.

“Oh no, but he loved Beatrice and was married to one Gemma Donati, whom he saw everyday. He saw Beatrice only once, in his entire life, and he loved her to the point that she accompanied him in his trip to paradise and back.”

(Image courtesy of AllPosters.com)

“Perfect number, three,” I reflect.

“You’re getting somewhere now,” she winks. “Consider this other line he wrote, ‘love, that releases no beloved from loving,’ it’s more beautiful in Italian of course, ‘amor ch’a nullo amato amar perdona.’ It’s been interpreted for the longest time, and nobody really knows what it means for sure. Does it mean that when A loves B, then B loves A? Namely, that when someone loves you completely you cannot escape that love, that if that love is true, you will recognize it and reciprocate it? Or does it mean the opposite, that when you are touched by the vital energy of eros because someone loves you, then you start loving someone, and so on and so forth. In other words, that loves is contagious but not necessarily reciprocal. As in, A, touched by the flame of eros, loves B; and B, when touched by the same flame, will love C, who, when touched by eros, will love D, who, touched, will love E, and so on and so forth, until, many, many plural loves later, the movement may come to a full circle.”

“OMG,” I exclaim. “But that’s very messy, and everybody gets upset, and it’s so unsettled.”

“I know,” G says. “Sounds like poly, uh?” she giggles.

“Sounds like poly to me,” I confirm.

“Well, Dante knew about it back in the fourteenth century.”

“Oh,” I wonder, “what evidence do you have?”

“This sentence, ‘love, that releases no beloved from loving,’ nobody knows what he intended because it really means both.”

“What do you mean both?”

“It’s ambivalent," she replies, "it means both the reciprocity of love, as in A loves B and viceversa, and the circulatory nature of erotic energies, as in A loves B loves C loves D loves E and so on. And all translators, readers, critics, theorists, have been baffled by it for centuries. Yet they all refer to it.”

“Oh, I get it, a literary trope.”

“You may say that. It’s more that the number three was in Dante’s mind, I think. He knew that perfect reciprocity is virtually impossible, that there is always some triangulation, even in the most perfect, most reciprocated type of love.”

“But then, that means that one cannot be really mono, because there is really no system of love that includes solely and exclusively two persons.”

“You’re beginning to get it. From one triangulation, to the next, to the next, to the next, all adjacent to one another, as in an Aids quilt one might say.”

“Then mono is poly. Granted, to some extent. But why is poly mono?” I ask her.

“That’s a little more complicated,” G replies. “Suppose you manage to be as mono as possible, to really focus on one person until s/he feels so loved that life comes to a standstill, that there is really nothing to desire any more.”

“Suppose . . . then what?” I ask.

“Then, from that experience, from having been present to that celestial, hyper-Uranian type of love, you can generate infinite compersion that allows you to love everyone like you’ve loved that person.”

“Ah, but . . . errrrr . . . wait a minute,' I respond, "I’m a bit confused. Sounds so philosophical, G, can you explain for us common mortals, my love?”

“Well, you know compersion. Compersion, that feeling that replaces jealousy, supposedly, in poly language? Well, it’s nothing really but a sublimation of desire into eros, a way to process the greed, the want for sex, for attention, into an ethereal energy that traverses time and space and expands that mono, that one-to-one reciprocity, to every person.”

“That sounds to me like creative energy. Art, creative expression, in all its forms, has some of that, no?”

“Yes,” G admits, “that’s the point. Especially art that’s part of a healing process, art that generates community, peace, joy. In fact, on might even say that all such art is a form of the arts of loving.”

“Handsome, G, thanks,” I offer.

“You’re welcome. What's on your mind?”

“Oh, well . . . it’s so extreme, so exaggerated. I’m not sure. Sounds like that story about demanding to test anonymously or not at all.”

“Oh, that’s right. You’ve not forgotten, uh?”

“No. Is this the lesson for the day? I’ll mull it over. Thanks for sharing. Now let’s get back to work. Keep me posted on developments. And when you test again, be a good patient, ok?”

The Three of Us, by Regina Reinhardt

End of G Tale # 1

Please note: The time references to some of the G Tales are off because they first appeared in SexGenderBody.

“The dichotomy between selfless and selfish love is deluded because affectional types of love are necessary for our survival as a species, and are therefore not as selfless as they are believed to be. It is self-defeating because all forms of love have an erotic component, the denial of which causes unhappiness and produces substantial amounts of hatred, often enough to defeat the forces of love.”

From Gaia and the New Politics of Love: Notes for a Poly Planet

Please note: The time references to some of the G Tales are off because they first appeared in SexGenderBody.

Reprinted here with thanks to Arvan Reese.

Friday, February 12, 2010

A Constellation of Books, Bi and Queer

“when bisexuality is “real” (in both a symbolic and a material sense), then the nature of love changes too . . . from an exclusive, dyadic system to an inclusive one that expands beyond the dual and into the multiple”

from Bisexuality and Queer Theory, “Introduction"

There’s news about G. She has been enjoying the tropical summer and has been reading.

She called me, “the summer has been beautiful” she said, “my first here, dressing up funny and enjoying a laugh with a bunch of local people.”

“What kinds of people?” I asked.

“All kinds, sexual diversity is exploding here, it must be the Spain effect, you know: Spain becoming so progressive in all kinds of queer issues. All across Latin America you can feel it: people are coming out, they are coming together, there is effervescence, excitement, thriving communities--I can’t believe it!”

“And what have you been doing?”

“Exporting bi and poly ideas, getting a good listening, feeling more situated, modeling three-way hugging and kissing.”

“And what else?”

“Well, you know what I do, what really reconnects me to myself: a good book! The kind of thing that really makes you feel connected with the person who wrote it, with the experience--that gives you that sense of symbiosis and synergy. I found several of these, bi books.”

She has been reading them with Jonathan Alexander, her colleague from UC Irvine, she explained, co-editor of the collection Bisexuality and Queer Theory, to be published soon.

“There was first a cluster of three, he sent me the draft, I read it, wrote into it, thought of two more books, added into the text then sent it back to him. He moved around some things: it was symbiotic the way our minds connected as we did it. And at one point it just flowed, it was perfect: something neither he nor I could have done alone.”

“The power of synergy,” I commented.

“You got it! That’s how we came up with the fiveway review you get here, courtesy of Routledge, the collection’s publisher. A constellation of books that love each other, and complement each other, and argue with each other, and get along with each other, like partners in a poly pod.”

G was thinking. “What’s your mind up to?” I asked.

“Have you heard of the latest poly feature on Newsweek? It was all over the news.”

“Oh yeah,” I reply, “So wonderful: filmmaker Terisa Greenan, in Seattle, revealing the configuration of her real life--not just film. Telling it like it is, modeling the beauty of what she and her partners have been building, offering it as a gift for the future, for a sustainable way of doing partnerships and relationships. What about it?”

“Well, it’s a bit like our fiveway review: first a cluster of three, then two more join the group.”

“But G! These are people, not books!”

“I know, I know, but books often express who we are most truthfully, they speak for us to the world and the future.”

“Ok, ok, you’re back on your literary spin. How incorrigible! I get it. And yes, it’s true, a pentagram, a cluster of five, it’s open, it’s abundant, it’s balanced, it’s one and many, like a star: there is magic to it.”

And so we decided to offer these book reviews to you.

The Constellation:

- Steven Angelides, A History of Bisexuality. University of Chicago Press, 2001. 281 pages (with index)

- Clare Hemmings, Bisexual Spaces: A Geography of Sexuality and Gender. Routledge, 2002. 244 pages (with index)

- Jennifer Baumgardner, Look Both Ways: Bisexual Politics. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007. 244 pages (with index)

- Jenny Block, Open: Love, Sex and Life in an Open Marriage. Seattle: Seal Press, 2009. 276 pages (with works consulted list)1

- Beth Firestein, ed, Becoming Visible: Counseling Bisexuals Across the Lifespan. Columbia University Press, 2007. 441 pages (with index)

- Reviews of these books will appear as "Reviews"

- Please note: The time references to some of the G Tales are off because they first appeared in SexGenderBody.

- Reprinted here with thanks to Arvan Reese.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)